NED KELLY - BUSHRANGER 1854 - 1880

Ned Kelly is Australia's best known bushranger, earning his reputation in various daring bank robberies during his short career, being described as a rogue and a villain by certain people, the man with the bucket on his head by others and Australia's last great folk hero by more sympathetic people.

The most memorable thing associated with Ned Kelly is the suits of armour worn by him and other members of the Kelly gang to protect themselves during shoot-outs with the police. Especially the head piece.

Ned kelly was the eldest boy of 8 siblings, attending school at Avenel, Victoria, but having to leave before he was 12 on the sudden death of his father. The death was a severe blow to the family. They eventually moved to a slab hut on Eleven Mile Creek, not far from Benalla and halfway between Greta and Glenrowan, an area which was later to become known as "Kelly Country". Ned being the eldest of the boys, it became inevitable for him to become a resourceful bush-worker while he was still a teenager. He did many things to earn a few shillings for the family, such as ring-barking, breaking in horses, mustering cattle and fencing. Many of the settlers in the area were small selectors who were at constant war with the big landowners who, at any time, could call on the forces of law and order to protect their interests. It is here that the key to Ned Kelly's rebellion against authority can be found. The police in the Kelly country also bitterly resented the clannishness of the small selectors and were determined to break them. In an official report made by a Superintendent Nicholson he stated firmly, if prejudicly: "The Kelly gang must be rooted out of the neighbourhood and sent to Pentridge gaol, even on a paltry sentence. This would be a good way of taking the flashness out of them." The forces of law had already been at work on the "Kelly gang", as Nicholson chose to call the family.

At the age of 14, in 1869, Ned was arrested for assaulting a Chinaman. After being kept in the Benalla lock-up for 10 days he was reluctantly released when the magistrate dismissed the charge. A year later Ned was again taken on a more serious charge, that of being an accomplice to the bushranger Harry Power. Again, the case against him was dismissed for lack of evidence. In 1870 he was again jailed for six months for throwing a hawker into a creek and in the following year, 1871, came disaster. He was sentenced to three years in Pentridge gaol for receiving a "borrowed" mare. The borrower was his friend Isaiah Wright, who unexplainably received a sentence of only 18 months!

A very embittered Ned was released in 1874 and made his way home. He found that his mother had re-married a man named George King, a Californian, and a horse thief. After giving Mrs Kelly 4 children he moved on. Ned had worked with him for a time, running stolen horses across the Murray River for sale in New South Wales. His younger brother Dan also got into trouble with the law while still in his teens. He was given 3 months for damaging property, but later the chief police witness against him was charged with perjury. On his release from prison Dan went home unaware that the police, unable to find King the horse thief, had sworn warrants against both Ned and Dan. Ned had slipped over the border into NSW. Fitzpatrick, the trooper who came with the warrant was newly enlisted. Before arriving at Mrs Kelly's place he stopped into a tavern. He found Dan at home with Mrs Kelly and the girls, as well as Will Skillion (Maggie Kelly's husband) and a neighbouring selector named Williamson. Fitzpatrick made a drunken pass at Kate Kelly. Dan knocked him down and, in the ensuing scuffle, the trooper's gun went off and he cut his wrist on the door-latch. Mrs Kelly was full of concern. She bandaged his wrist and he was invited to have supper with the family and "let bygones be bygones." On his way back to police barracks, Fitzpatrick had some more brandy. He then reported to his superiors that Dan Kelly had resisted arrest, and that Ned had burst into the room and shot him in the wrist. By the time a troop of police had arrived at the Kelly place and surrounded it Dan had gone into the bush. In spite of Mrs Kelly's protests that Ned was 400 miles away and that nobody had shot Fitzpatrick, arrests were made. For assisting in the attempted murder of a police officer, Skillion and Williamson were given six years each, and Mrs Kelly herself was sentenced to three years in gaol. Later, Fitzpatrick was discharged ignominiously from the police force for misconduct in another case. But by then the damage had been done.

Ned Kelly came storming back across the Murray, swearing vengeance. Restrained by his friends, he instead wrote an impassioned letter to Magistrate Wyatt, offering to surrender his own person "to any charge" in exchange for his mother, but Wyatt was powerless to act. By then the police were increasing their efforts to get Ned Kelly, so he and Dan vanished overnight from the district. The government offered a reward of £100 each for their apprehension. Ned and Dan went into hiding in the Wombat Ranges, some 20 miles from Mansfield in rough country. The police hunt intensified and, in October 1878, Sergeant Kennedy, with Constables Lonigan, Scanlon and McIntyre, rode out from Mansfield. They wore no uniforms but all were heavily armed.

On October 25 they camped at Stringy-bark Creek, not knowing it was only a mile from Kelly's camp. Making one of his regular reconnoitres, Ned spotted the police camp and hurried back to raise the alarm believing, rightly or wrongly, that he and Dan would be shot on sight. The next day, Sergeant Kennedy and Scanlon rode out on patrol, leaving Lonigan and McIntyre in camp. The two troopers were relaxing by the campfire when Ned and Dan emerged silently from the bush. They challenged the troopers and ordered them to "bail up". Lonigan jumped to his feet and drew his revolver but Ned shot him dead. McIntyre surrendered immediately. When Kennedy and Scanlon returned to the camp they immediately opened fire. A gunfight followed, with the policemen dodging from tree to tree. Ned, whose shooting was deadly even in the fading light, killed Kennedy and Scanlon but McIntyre managed to escape on Kennedy's horse. When Hart and Byrne joined the Kellys, they covered the bodies of the police troopers with blankets, broke camp and rode out.

Constable McIntyre reached Mansfield to raise the alarm and told a story of a cowardly ambush by the Kellys and a mass slaughter, which shocked Mansfield and, in time, the whole country. Ned Kelly, Dan Kelly, Steve Hart and Joe Byrne were proclaimed outlaws, to be taken dead or alive. Two hundred police were drafted into the area and skilled blacktrackers were brought in from Queensland. The police manhunt drew a blank. Even with emergency powers to enter premises, search and arrest without warrant, the police could find no trace of the Kelly gang. Suspected sympathisers were arrested and held for weeks on remand. Public sympathy for the police vanished and resentment set in, even among law-abiding citizens who deplored the shooting of Kennedy and his men. Then at last the police got help from a friend of Joe Byrne named Aaron Sherritt, who turned informer. Ned Kelly and his gang escaped by a matter of hours. They had friends everywhere, but they had no money. Ned decided that funds must be raised to keep them going and to help sympathisers who needed bail money.

On December 10, 1878, the Kelly gang invaded a station property near Euroa, 27 miles west of Benalla. Twenty-two people at the sheep-station were rounded up and locked in a storeroom while the Kellys' horses rested. Then, leaving Byrne to guard the prisoners, Ned, Dan and Steve Hart drove into Euroa in a commandeered hawker's cart. Euroa then had a population of no more than 300, with an unpretentious National Bank building on the main street. At 4 pm Ned Kelly entered the bank with a drawn gun, and Dan came in from the rear. Ten minutes later they were out on the street again, richer by £2,000 in notes and gold. The Government of Victoria then increased the rewards on the heads of the Kelly gang to £1,000 each, and military guards were posted on all banks in the north-eastern district. Two months later, Ned Kelly and his men crossed the border into NSW and struck again. This time their target was the Bank of NSW at Jerilderie. It was a Saturday night and they captured the two local policemen and locked them up. Then they dressed themselves in police uniforms and stabled their horses. Next day, Ned supervised the rounding-up of more than 60 townspeople in the dining room of the Royal Hotel, next door to the bank. Then he dictated a document which he intended should be read by all the world. It was a remarkable document - autobiography, statement of fact and self-justification - which ran to 8,300 words. On Monday morning, when the statement was finished, Ned went in search of the local newspaper editor to have it printed, but the editor had gone into hiding. Carefully checking to make sure all the telephone wires out of town had been cut, Ned then proceeded to rob the bank. The Bank of NSW lost over £2,000 in notes and coin that day. Ned gave his manifesto to one of the tellers, who swore he would give it to Donald Cameron, MP, but instead he passed it on to the Crown Law Office in Melbourne. The statement was then carefully put away and was not produced at Kelly's trial; nor were its contents made known to the press. It was not made available to the public until the 1930s, and may now be read in the Public Library in Melbourne.

It is believed that after 'Jerilderie the Kelly gang went into hiding in the Bogong high plains. By then there was a price of £8,000 on their heads, but they still managed to stay free for 16 months. They came out of hiding in June 1880 and returned to their own country. But the police were alerted and at last the Kellys knew who had informed on them. One night Aaron Sherritt opened his door to find Joe Byrne standing there. Without a word, he shot Sherritt dead. Four armed guards had been deputed to protect Sherritt who, by then, was on the police payroll. Byrne and Dan Kelly challenged them to come out and fight but the troopers declined, and the two outlaws rode 40 miles across country to join Ned and Steve Hart at Glenrowan.

On Saturday, June 27 1880, the Kelly gang captured the railway station at Glenrowan. A crowd of people from the tiny railway town was taken into Mrs Ann Jones's Hotel (who Ned suspected of being a police informer) near the station. The local policeman (Constable Bracken) was made a prisoner and the telegraph wires were cut. The Kellys had not slept for two nights but only the resourceful Constable Bracken and the school teacher, Thomas Curnow, were able to outwit them and escape. A train crowded with police left Melbourne for the Kelly country at 10.15 pm that Sunday. In the early hours of next morning the whistle of the approaching train could be heard. The Kelly gang waited for the sound of derailment (as earlier Ned had ordered a railway fettler to tear up a section of the railway track) but it never came. Curnow, the school teacher who had escaped, had run along the track and stopped the train before it reached the rail break. Ned Kelly put on his armour which was hammered out from plough-shares, consisting of a cylindrical helmet, a breastplate with apron and a backplate laced with leather thongs. The armour weighed 90 lb. It was around 3-00am and the police moved among the trees surrounding the hotel and as they were taking up their firing positions the Kelly gang came out and started shooting. In the exchange of fire, Ned Kelly was shot in the foot, hand and arm and escaped into the trees. Joe Byrne was shot in the leg, and he and the two others retreated into the hotel. The women and children pinned inside were screaming, but the police kept up a murderous fire. Inside, Dan Kelly ordered the townspeople to lie flat and not to raise their heads. The exchange of bullets continued until dawn started breaking and the townspeople who were by then almost hysterical, started to brave the police barrage and come out. Mrs Reardon, clutching a shawl round her baby, stepped out from the hotel veranda. She heard a policeman, afterwards identified as Sergeant Steele, call out, "Throw up your hands or I'll shoot you like a bloody dog!" Mrs Reardon ran forward. Steele fired and the bullet passed through the shawl, missing the baby by inches. Two other children were not so lucky. One was wounded and another shot dead, and another youth was wounded only a few minutes later.

As the sun rose, a limping Ned Kelly in his dented armour, gun in hand, started to come out from the bushes. Bullets were clanging on his armour as he walked slowly towards the police. A senior constable, also named Kelly, decided to fire at Kelly's legs and at last he fell. Within minutes police had surrounded Ned. They cut the thongs to free Ned from his armour and his face was a mask of blood. He had so many wounds they thought he would not live, and so carried him into the railway station.

With the sunrise another train arrived in Glenrowan and one of its passengers was Father Matthew Gibney, a Roman Catholic priest. Ned Kelly's sisters, Kate and Maggie, begged him to see their brother and give him the last rites. Father Gibney found the outlaw conscious and comforted him and then went to the hotel. The police thinking all the townspeople were out of the hotel fired the building with straw soaked in kerosene. Someone cried out that Martin Cherry, a townsman, was trapped inside with the outlaws. So with great courage, Father Gibney went into the blazing building with hands raised high to show he was unarmed. But no shots came. Gibney fought his way through to a back room and there found the lifeless bodies of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart. Giving evidence later at the official inquiry, the priest gave it as his opinion that the outlaws had committed suicide, probably by taking poison. The bodies lay side by side, heads propped on folded blankets. Martin Cherry was rescued but later died.

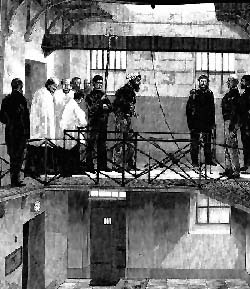

Dan Kelly and Steve Hart were buried in Greta cemetery. Ned Kelly was taken to Melbourne, to pass through streets crowded with people. When they found him fit to stand trial the sentence of death was passed (The judge was Sir Redmond Barry, the Chief Justice, who had once made the grim promise that he would see Ned Kelly hang) Ned Kelly replied, "I'll see' you where I'm going, Judge." Twelve days later, Judge Barry dropped dead in his chambers. On November 11 1880, as the hangman adjusted the hood to cover Ned's face, his last words were: "Such is life." Mrs Kelly's last words to her son Ned were, "Mind you die like a Kelly, Son!" She survived until 1923, dying at the age of 92. So at the young age of 25 Ned Kelly was executed and died.

Ned Kelly being led to the gallows at the Old Melbourne Jail.

And this is the story of Ned Kelly. Now you can make up your own mind whether you think he was a young thug voluntarily prefering crime to doing honest work, who killed people without mercy and who deserved to die the way he did OR whether you think he was a victim of a vicious system, a young man hounded into crime by the prejudices and injustices of certain people, in his case the forces of supposed law and order, and whose death fell little short of martyrdom. What do you think of this Australian-Legend and Folk-Hero? The saddest thing for me is knowing that this type of prejudice and injustice still exists today in our forces of law and order. We should be able to trust them explicitly and know that they will protect us, but this small minority group, who through their stupidity, inhumanity and retrograde still continue to believe in prejudice, are the ones that give the rest of the force a bad name thus making it very hard for the people to have complete trust and confidence in them.

If you are interested

in reading more about Ned Kelly please go to

NED KELLY-IRON OUTLAW-THE

AUSTRALIAN LEGEND